Shelter from the storm: recent countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) decisions

Published as part of the Macroprudential Bulletin 7, March 2019.

When living by the ocean, instead of trying to calm the waves and tides, building a levee or a breakwater is the safest option. This article reviews the country-specific strategic choices and decisions regarding timing and calibration of the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) in countries participating in the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). It identifies commonalities across countries and country specificities that influence decisions by national designated authorities. In so doing, it summarises the limitations encountered with the credit-to-GDP gap and the role of other indicators and factors in calibrating the appropriate CCyB rate on the basis of “guided discretion”. Ultimately, assessing risks across euro area countries consistently, while taking into account country-specific factors, supports the effective use of the CCyB as a macroprudential instrument and ensures that similar risk exposures are subject to the same set of macroprudential requirements.

1 Introduction

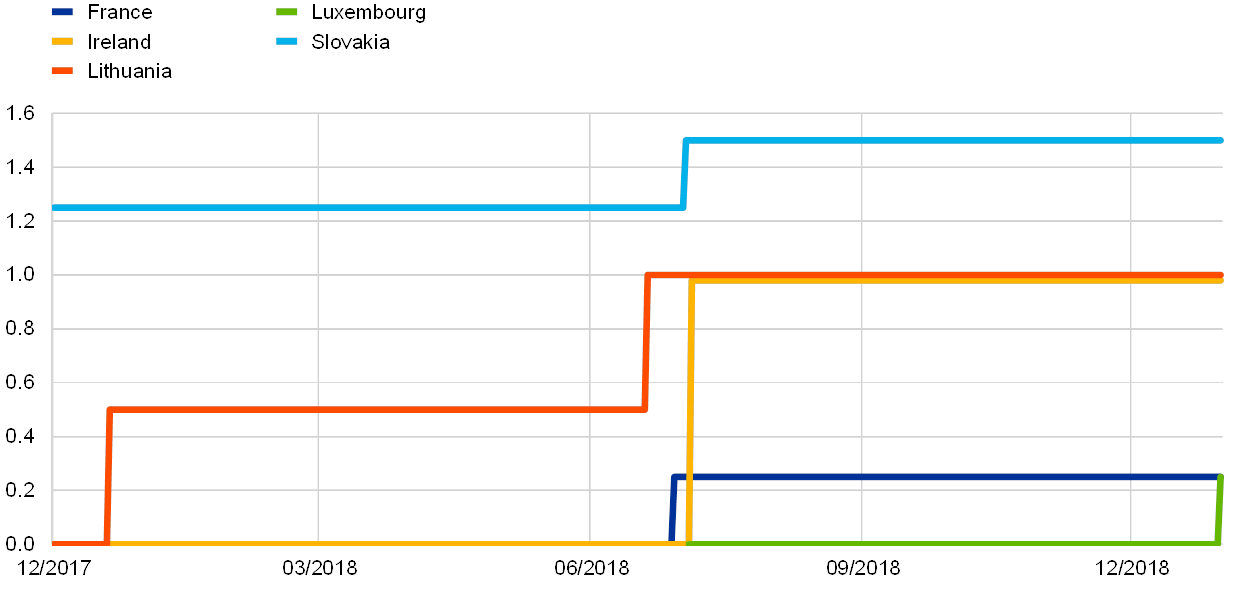

The countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) has been increasingly set to positive rates across euro area countries. In the course of 2018, national designated authorities in France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Slovakia announced CCyB rates of between 0.25% and 1.5%. Buffer requirements are implemented with a lag of four quarters after their announcement, and until February 2019 CCyB rates were zero in all euro area countries, except Slovakia (1.25%) and Lithuania (0.5%) which had already announced rates previously.

The CCyB is predominantly aimed at building resilience in the banking sector, commensurate to the prevailing cyclical systemic risk. Its legal basis is the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) as transposed into national law, while its calibration is based on the principle of “guided discretion”, following BCBS guidance and Recommendation ESRB/2014/1.[1] Guided discretion implies that macroprudential policymakers employ buffer guides based on risk indicators and apply discretion based on a range of economic and financial variables together with qualitative assessments.[2]

Current regulation emphasises the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its estimated long-term trend, known as credit-to-GDP gap or Basel gap, as a basis for the buffer guide.[3] While the Basel gap is broadly considered to provide good early-warning signals for historical systemic banking crises, it faces shortcomings of particular relevance in the current environment. Namely, after long credit expansions, the credit-to-GDP gap tends to have a downward bias that stretches far into the crisis aftermath. The longer the pre-crisis credit expansion, the greater the credit excesses contained in the underlying credit-to-GDP trend. As a result, the trend is higher in the upturn, which underestimates the positive gap. Conversely, after the crisis, the trend remains elevated for a protracted period of time which results in a larger negative gap value. Furthermore, the gap is sensitive to the length of the underlying time series, especially if the time series are short as is the case for many European countries.[4]

In the current environment, for all except two of the euro area countries, the credit-to-GDP gap is below 2 percentage points, which is seen as the activation threshold set by international institutions.[5] Only in France and Slovakia was the standard Basel gap higher at the time the CCyB rate increases were announced in 2018 (at 3.8 and 3.9 percentage points, respectively, which would imply buffer guides of 0.5% and 0.75%, respectively). This shows that the use of the credit-to-GDP gap when deciding CCyB rates requires discretion, which may pose communication challenges both at national level and when comparing CCyB rate settings across countries.

Communication on the national CCyB frameworks provides strategic insights for the calibration of the CCyB and can expose elements of discretion.[6] The CCyB frameworks include choices to be made by macroprudential authorities on the risk assessment, the decision-making process, and ultimately on the calibration of CCyB rates. While resilience appears relevant in all frameworks, there are slight differences in the relative importance of building resilience and taming the cycle. Generally, the frameworks imply building up the CCyB gradually in order to effectively anticipate an adverse shock to bank capital. These strategic elements are combined with detailed information on cyclical systemic risk in the context of CCyB decisions. Few national authorities formally consolidate the risk information contained in the individual indicators. As a consequence, this involves discretion to establish their relative importance.

The ECB’s role in this context is to assess the appropriateness of the CCyB decisions notified by national authorities.[7] Under the SSM Regulation, the ECB’s responsibility is to regularly assess the national CCyB rates and, if needed, to apply higher requirements for capital buffers than those applied by national authorities. The national frameworks guiding the use of the CCyB are a key element taken into account by the ECB when conducting its assessment. Furthermore, the ECB’s assessment complements national risk and policy assessments with a cross-country perspective. In this way, the interplay of the national authorities and the ECB provides a robust assessment of risks and ensures an appropriate calibration of CCyB rates in the countries participating in the SSM, thereby contributing to an efficient banking union with a consistent approach to cyclical systemic risk.

The increased use of the CCyB across countries has led to a greater focus on its analytical underpinning, the methodological toolkit used, and its potential impacts. As far as risk assessment is concerned, the focus is on both the role and the effectiveness of cyclical systemic risk indicators in identifying the appropriate timing for activation as well as in guiding the calibration itself. This has led to the proposal of complementary reference indicators and methodologies for determining the financial cycle.[8]

The remaining sections of this article are structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the decisions made in euro area countries during 2018 with an emphasis on their strategic choices and the activation environment, and Section 3 examines the calibration of CCyB rates. Finally, Section 4 compares the decisions in their assessment of the potential impact and transmission channel.

2 CCyB decisions in more detail

The decisions taken in 2018 to increase CCyB rates provide an opportunity to compare country-specific strategic choices. Among the SSM countries, positive CCyB rates have been set in France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Slovakia (see Table 1). The decisions made by the national designated authorities to increases the rates in 2018 all make reference to the objective of enhancing the resilience of the banking or the financial sector and refer to the concept of cyclical systemic risk. The decisions nevertheless differ in the relative weights given to the objectives of building resilience and mitigating excessive credit growth.[9] Furthermore, in Ireland, Lithuania and Slovakia, the real estate sector played an important role in the assessment of cyclical systemic risk and in motivating the CCyB calibration. Notwithstanding these similarities, the decisions reveal cross-country differences related to the specific timing of activation, the size of the initial activation and considering risks to the financial system as cyclical or structural.

Table 1

CCyB decisions in SSM countries in 2018

Source: Notifications of CCyB rates, ESRB website.

Notes: The reference credit gap available at the decision date is usually from two quarters previously. Data last updated 8 January 2019. Retrieved from website 25 January 2019.

In Lithuania the increase of the CCyB rate from 0.5% to 1% by Lietuvos bankas was guided by the change in guiding principles previously announced in December 2017.[10] These guiding principles indicate maintaining a base rate of around 1% when the economy and the financial system are in a moderate risk environment. This moderate risk environment is defined as a “situation when credit and real estate markets are active, economic growth is close to (or above) its potential growth, the banking sector operates profitably and no cyclical imbalances form”. Lietuvos bankas implemented its strategy by raising the CCyB in two steps of 0.5% each, first in December 2017, followed by the announced increase in June 2018. The decisions are implemented with a 12-month lag, in line with the legal provisions. The strategy implies that CCyB rates can increase well ahead of mounting imbalances in the banking sector and thus offer an opportunity to support the banking sector against unforeseen impairments.

In the case of Ireland, the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) increased the CCyB to 1% in one step, before marked exposures to cyclical systemic risk became broadly visible in standard risk indicators. The CBI justified the decision by emphasising the forward-looking aspects of the risk assessment and the forward-looking role of the CCyB. By activating early in the cycle, the CBI is seeking to pre-empt the relatively “large amplitude of the financial cycle” observed in the past and considers that “resilience is most effectively maintained by moving early in the cycle”.[11] The exposure to external shocks in combination with large non-performing exposures and debt overhang created additional vulnerabilities for the Irish banking system and would amplify the risk build-up.

In Slovakia the CCyB rate has been steadily increasing since the second quarter of 2017, keeping pace with the risk in the financial cycle with the latest decision to raise CCyB rates from 1.25% to 1.5%. In contrast to Lithuania and Ireland, the CCyB increases in Slovakia occurred in response to the financial cycle’s continuing expansionary phase. The decision by Národná banka Slovenska (NBS) was intended to complement the existing borrower-based instruments. While the borrower-based measures address lending flows and lending conditions, the additional capital buffers help attenuate potential impacts on balance sheets should risks materialise. NBS sought to strengthen banking sector resilience as banks were trying to offset an interest margin squeeze by increasing lending volumes.

France and Luxembourg activated the CCyB for the first time, responding to the strengthening upturn in the financial cycle. They did so by increasing the rate by 0.25%. The preventive nature of macroprudential policy and the favourable macroeconomic context – with forecasts of above-potential growth in the coming years – were cited as some of the driving forces for the decision. In the view of the Haut Conseil de stabilité financière (HCSF),[12] an increase of the minimum step size of 0.25% was justified given the gradual increase in systemic risk, remaining uncertainties surrounding the risk assessment, and the intention to reduce adjustment costs for banks, especially those with tighter excess buffers.[13] In Luxembourg, the assessment by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF)[14] showed that the further acceleration of credit in the current macroeconomic environment “is likely to be a potential source for systemic risk”.[15] At the same time, however, bank resilience measured by the level of capitalisation or leverage remained stable.

The decisions in the five countries reflect different strategic choices. The strategies of the authorities in Lithuania and Ireland reflect the intention to secure a capital buffer early in the build-up of cyclical systemic risk, which is particularly important given the identified risk amplification mechanisms. For the authority in Slovakia, facing a larger cyclical systemic risk, it was important to closely follow the changing risk dynamics. Meanwhile, the authorities in France and Luxembourg announced smaller rate sizes, reflecting a more contained build-up of risks.

The decisions by the five authorities illustrate the communication challenges facing macroprudential policymakers. Namely, building the appropriate countercyclical buffer when the authorities identify the slow build-up of cyclical systemic risk needs to be carefully communicated, without unintentionally fuelling risk perceptions that could destabilise financial markets through self-fulfilling dynamics. This is perhaps most apparent in decisions on CCyB rates that are not strictly tied to a buffer guide.

Chart 1

Decisions to increase CCyB in 2018

(announced CCyB rate to be implemented in four quarters)

Source: Notifications of CCyB rates, ESRB website.

Notes: Data last updated 8 January 2019. Retrieved from the website 25 January 2019.

Policy environment and interaction

In addition to the risk indicators focusing on the financial/credit cycle, policymakers also consider the overall environment of macroprudential policies. This involves assessing the interplay of risks and resilience in the financial system, as summarised in the macroprudential stance.[16] Other implemented macroprudential instruments play an important role and may influence the specific calibration of the CCyB rate. For example, while the CCyB seems to be viewed as the right instrument for enhancing the resilience of the banking system, borrower-based measures might more efficiently target the flow of new lending and the resilience of borrowers.[17]

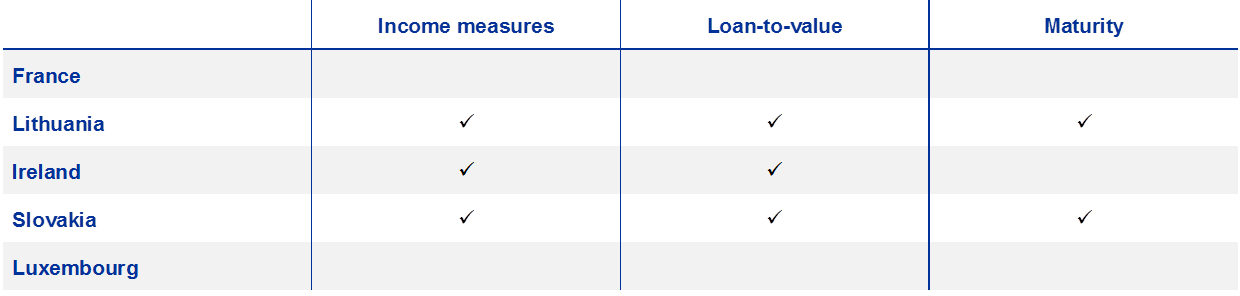

In the majority of the countries which activated or raised the CCyB during 2018, the instrument seems to be viewed as a complement to other measures (Table 2). The CCyB complements the borrower-based measures in Ireland “by mitigating the impact of risk taking in non-mortgage lending”.[18] In Slovakia, Národná banka Slovenska considers it to complement the existing borrower-based instruments, thus “addressing strong lending flows and lending conditions with stronger capital buffers to attenuate the potential impact of risks”.[19] These explicit references reflect the CCyB’s place in the macroprudential toolkit of these countries.

Table 2

CCyB and borrower-based measures

Source: Banco de Portugal.

Notes: See Financial Stability Report, Banco de Portugal, December 2018, Chart C3.1 (which in turn cites the ESRB).

3 Rate calibration

In a number of SSM countries in the current environment, the buffer guide based on the credit-to-GDP gap appears to have a limited role in informing the CCyB calibration. As mentioned earlier, the credit-to-GDP gap, which the Basel guide is based upon, shows signs of a downward bias. The strong, largely unsustainable pre-crisis credit growth embedded in the trend component has caused the current, more moderate credit-to-GDP levels to appear deeply subdued.[20] As a result, the guide indicates a value of zero for the CCyB rate. Chart 2 compares past CCyB rate announcements with credit-to-GDP gaps between 2014 and 2018 for those countries in which the credit gap or the CCyB rates have been positive. The diagonal line indicates full alignment between the Basel guide and CCyB rate announcements and could be interpreted as indicating that the authority follows the Basel guide closely. Deviations from the diagonal, on the other hand, indicate the importance of discretion and in case of negative deviations potentially also an inaction bias.

Chart 2

Basel guide in practice from 2014 to 2018

(percentages)

Source: Notifications of CCyB rates, ESRB website.

Notes: Dots denote different points in time, especially when the CCyB rate diverged from the Basel guide. Belgium and Finland are included, as at different points in time their buffer guides pointed to a positive buffer rate. Some data points may overlap and are thus not visible. Data last updated 8 January 2019. Retrieved from the website 25 January 2019.

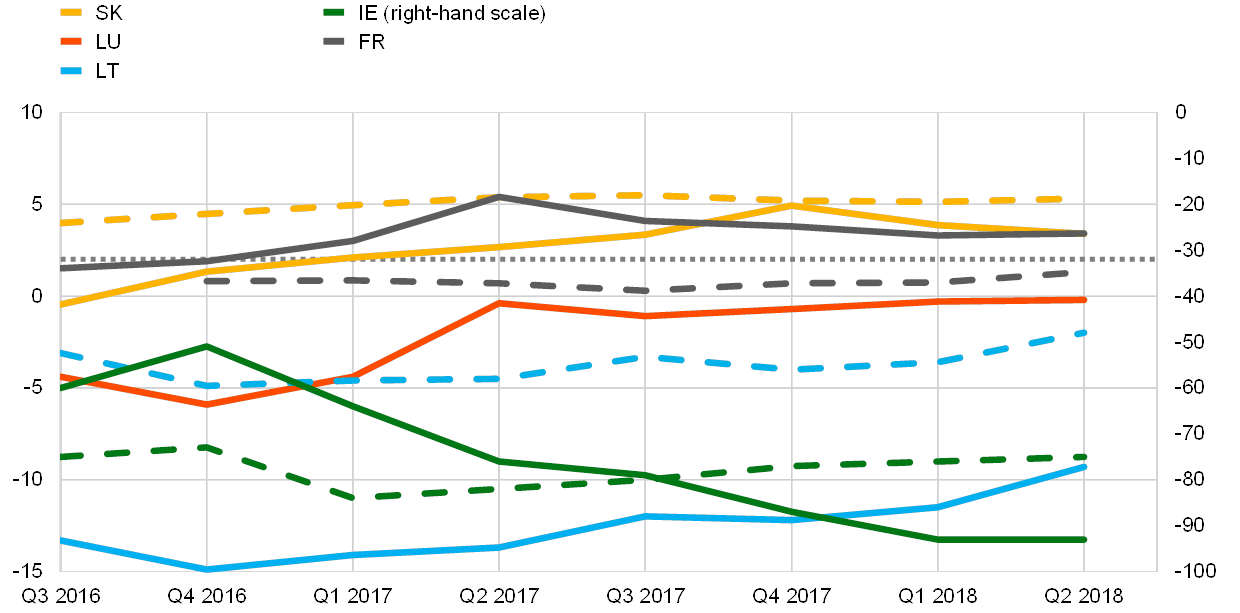

In 2018, only in France and Slovakia did the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its long-term trend imply a positive CCyB rate. Even in countries where the credit-to-GDP gap is positive, it appears to have a rather limited role in informing the calibration of the CCyB rate (Chart 2). In Slovakia, at the time the rate was raised from 1.25% to 1.5%, the latest available standardised credit gap would have implied a CCyB rate of 0.75% (see Chart 3).[21] In other countries, the credit-to-GDP gap remains negative. In Luxembourg, the Basel gap is mildly negative but slowly approaching positive values. In Ireland, the Basel gap remained deeply negative for quite some time, while the alternative measures of the credit gap, preferred by the national authority, showed it to be “trending back to zero at a more significant pace”.[22]

Apart from having a limited influence on decision-making, the Basel gap seems to provide further challenges to policymakers. Chart 3 depicts the Basel gaps and nationally-preferred versions thereof (dashed lines) published by national designated authorities together with their quarterly CCyB decisions. Due to the data lags, the latest available credit gap data are usually from two quarters before the decision. For instance, in Slovakia the CCyB was increased in the third quarter of 2018 based on the declining Basel gap from the first quarter after a period of strong growth. This data lag could be challenging for communication if the argumentation for a particular decision is heavily built on the level of the Basel gap, which might decrease or be revised afterwards. Such a policy error or a revoked build-up could potentially tarnish institutional reputation.

Chart 3

Credit-to-GDP gaps notified quarterly by the authorities

(credit-to-GDP gap, percentage points)

Source: Notifications of CCyB rates, ESRB website.

Notes: Dashed lines represent nationally preferred variants of the Basel gap. The dotted line represents the 2 percentage point activation threshold. Data last updated 8 January 2019. Retrieved from the website 25 January 2019.

Given the shortcomings faced by the Basel gap, national authorities have developed alternative methods to inform the CCyB calibration.[23] In particular, given the downward bias in the credit-to-GDP gap (see Section 1), authorities use other measures of financial cycles or composite indicators of cyclical systemic risk. Some authorities go as far as also publishing, in addition to the individual indicators, the rates implied by these additional reference indicators, such as Slovakia, which has a composite financial cycle indicator, the Cyclogram.[24] These provide alternative guidance and can thus ease external communication and enhance transparency.

As the main objective of the CCyB is to build resilience in the banking sector, its size is related by some authorities to the losses should risks materialise. For instance, the calibration of the 1% rate to be attained in normal times for exposures to Lithuania was indicated by Lietuvos bankas’ assessment based on stress testing methodologies. Specifically, the assessment indicated that bank losses from historical economic downturns amounted on average to 1% of risk-weighted assets. Similarly, in Ireland, the CCyB level is in general guided by the “level of resilience expected to be sufficient to support the sustainable provision of credit to the real economy in a subsequent downturn”.[25]

In addition to guiding indicators, authorities use multiple approaches to assess the impact of CCyB rates and to ensure loss absorption in an adverse scenario. Some authorities involve DSGE models to calibrate the CCyB by optimising a given objective related to the credit cycle or the banking sector. In addition, a hybrid strategy based on stress-testing and time series models entails assessing the impact of a specific macroeconomic scenario on the banking system and potential capital shortages. The policy impact of a calibrated CCyB rate is then fed back into the scenario itself, providing a feedback loop.[26] A suite of models is therefore useful not only for the risk assessment but also for the assessment of the impact of a CCyB calibration and for the conduct of risk scenarios.

4 Impact assessments and policy transmission

Policymakers’ decisions are also influenced by the projected impact of the policy on the real economy and the banking sector. Naturally, policymakers estimate the potential benefits and costs of a macroprudential policy. For instance, an adjustment path towards the new capital requirement that requires banks to deleverage or to raise capital might be costly or destabilising in a specific risk environment. Instead, a gradual increase of the CCyB rates in order to raise capital ratios through retained earnings and dividends or the availability of voluntary/management capital reduces the potential impact of an increase in the buffer requirement. The decisions in Lithuania and Ireland to raise the CCyB to 1% have also been helped by the fact that banks hold sufficient “headroom” to accommodate the increase in capital requirements given the fair profitability.

Lietuvos bankas assessed the impact of the 0.5 percentage point increase in the CCyB in December 2017 as potentially increasing the cost of borrowing by 0.07 percentage points while reducing annual credit growth by 0.5 percentage points. However, it estimated that the potential negative impact on the economy “would practically wane”.[27] In June Lietuvos bankas estimated the effects of a further increase to 1%, which has been announced consistently since December, to be “marginal” as “the absolute majority of financial institutions already now hold capital sufficient to meet the above-named requirement”.[28]

Similarly, in Ireland the “existing headroom in the capital of the banking sector” was an important factor influencing the calibration of the CCyB rate, a decision entailing a relatively large step to increase the CCyB by 1 percentage point (from 0% to 1%), reflecting “the expected limited impact on the credit environment and real economy at this stage”. Such expectations were based on a structural model which found that, even if a CCyB increase of 1 percentage point was binding for banks’ ex-ante existing capital ratios, it “would not necessarily result in significant short-run ‘costs’ in terms of economic activity foregone”.[29]

Other authorities consider potential CCyB impact differently. In France, the aforementioned hybrid buffer rate calibration strategy formally assesses the impact of a proposed CCyB rate on the real economy and the banking sector, thus featuring a feedback loop back to the original scenario. In this manner, the impact assessment is internalised in the decision-making process. In Slovakia, due to the phase of the cycle, authorities recently focused on the instrument’s impact in fulfilling the objective of raising resilience. The NBS pointed to “one of the lowest gaps between the capital requirements and the sector’s total capital ratio” in the EU.[30] This observation, combined with the concerns over recent banking margin compression which “has been eroding banks’ capacity to use current earnings to cover any cyclical losses”, influenced the decision to increase the CCyB.[31]

5 Conclusion

The calibration of the CCyB rates is based on “guided discretion”, which combines guidance from key risk indicators and more discretionary elements reflecting specific economic and financial conditions. The guidance has a role in steering CCyB decisions in the presence of credit-related cyclical systemic risk to help overcome a potential inaction bias. As revealed by the discrepancies between the signals stemming from the credit-to-GDP gap and CCyB decisions in the euro area, policy guides based on the credit-to-GDP gap currently play a more limited role in CCyB decisions (Charts 2 and 3). As a result, discretionary elements based on other indicators are important in calibrating the appropriate CCyB rate. The limited guidance and the more extensive discretion make external communication more challenging.

A consistent assessment of risks across euro area countries, while accounting for country-specific factors, supports the effective use of the CCyB as a macroprudential instrument. The consistent use of additional risk indicators over time and across countries can help make macroprudential policy more predictable. Relying on a consistent approach to analysing risks and to integrating country-specific factors can raise the transparency of setting CCyB rates. An important role has been given in the examples to the adaptability of the banking sector or the phase of the financial cycle, the structure of a country’s banking system, indebtedness level, the phase of financial deepening, and the degree of economic openness, all of which influenced the aforementioned CCyB decisions. Transparent communication on these factors and their relevance for the CCyB calibration helps to better steer market expectations, to the degree that it provides credible “forward guidance”.[32]

Transparent and consistent calibration of CCyB rates across the euro area supports the overall functioning of the banking union. It ensures that similar risk exposures are subject to the same set of macroprudential requirements, net of relevant country specificities. The consistent application of the capital buffers based on the CRR/CRD IV capital framework strengthens the overall understanding and functioning of the framework, helps to ensure accountability and ensures a level playing field which underpins the mandatory reciprocity of CCyB calibrations up to 2.5%.

References

Babić, D. (2018), “Special feature B: Use of the countercyclical capital buffer – a cross-country comparative analysis”, A Review of Macroprudential Policy in the EU in 2017, ESRB, August 2018, pp. 68-82.

Bennani, T., Couaillier, C., Devulder, A., Gabrieli, S., Idier, J., Lopez, P., Piquard, T. and Scalone, V. (2017), “An Analytical Framework to Calibrate Macroprudential Policy”, Working Paper, No 648, Banque de France, October.

Castro, C., Estrada, Á. and Martínez, J. (2016), “The countercyclical capital buffer in Spain: an analysis of key guiding indicators”, Working Papers, No 1601, Banco de España.

CBI (2016), Information Note: The application of the countercyclical capital buffer in Ireland

CBI (2018a), “Countercyclical capital buffer rate announcement”, 5 July 2018, retrieved 20 January 2019.

CBI (2018b), “Countercyclical capital buffer rate announcement”, 27 September 2018.

Clancy, D. and Merola, R. (2017), “Countercyclical capital rules for small open economies”, Journal of Macroeconomics, Vol. 54, 2017, pp. 332-351.

Couaillier, C., and Idier, J. (2017), “Measuring excess credit using the “Basel gap”: relevance for setting the countercyclical capital buffer and limitations”, Quarterly selection of articles – Bulletin de la Banque de France, No 46, Banque de France, pp. 5-18.

Detken, C., Fahr, S. and Lang, J. H. (2018), “Predicting the likelihood and severity of financial crises over the medium term with a cyclical systemic risk indicator”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May, pp. 164-88.

ECB (2010). “Comparing macro-prudential policy stances across countries”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, December, pp. 133-7.

ECB (2017), “Activation of the Countercyclical Capital Buffer - A survey on strategies by countries with positive CCyB rates”.

ESRB (2017), The ESRB Handbook on Operationalising Macro-prudential Policy in the Banking Sector, Chapter 2, pp. 25-47

Fahr, S. (2018), “Lessons from CCyB decisions in SSM countries: a cross-country perspective”, Macroprudential Report, ECB, December 2018.

HCSF (2018), Press release Paris, 11 June 2018.

Lang, J.H. and Welz, P. (2017), “Measuring credit gaps for macroprudential policy”. Financial Stability Review, ECB, May.

Lang, J.H., Izzo, C., Fahr, S. and Ružička, J. (2019), “Anticipating the Bust: A New Cyclical Systemic Risk Indicator to Assess the Likelihood and Severity of Financial Crises”, Occasional Paper Series, No 219, ECB.

Lietuvos bankas (2015), “Application of the countercyclical capital buffer in Lithuania”, Teminių straipsnių serija, No 5/2015.

Lietuvos bankas (2017), Countercyclical capital buffer: Background material for decision, December.

Lietuvos bankas (2018a), Countercyclical capital buffer: Background material for decision, March.

Lietuvos bankas (2018b), Countercyclical capital buffer: Background material for decision, June.

Lietuvos bankas (2018c), Countercyclical capital buffer: Background material for decision, September.

Lietuvos bankas (2018d), Countercyclical capital buffer: Background material for decision, December.

Lozej, M. and O’Brien, M. (2018), “Using the Countercyclical Capital Buffer: Insights from a structural model”, Economic Letters, Vol. 18. No 7, Central Bank of Ireland.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018a), Quarterly commentary on macroprudential policy, January.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018b), Quarterly commentary on macroprudential policy, July.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018c), Quarterly commentary on macroprudential policy, October.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018d), Financial Stability Report, November.

O’Brien, E. and Ryan, E. (2017), “Motivating the Use of Different Macro-prudential Instruments: the Countercyclical Capital Buffer vs. Borrower-Based Measures”, Economic Letters, Vol. 2017, No 15, Central Bank of Ireland.

O’Brien, E., O’Brien, M. and Velasco, S. (2018), “Measuring and mitigating cyclical systemic risk in Ireland: The application of the countercyclical capital buffer”, Financial Stability Notes, No 4, Central Bank of Ireland,

Pekanov, A. and Dierick F. (2016), “Implementation of the countercyclical capital buffer regime in the European Union”, ESRB Macroprudential Commentaries, No 8, ESRB, December.

Reigl, N. and Uusküla, L. (2018), “Alternative Frameworks For Measuring Credit Gaps And Setting Countercyclical Capital Buffers”, Working Paper Series, No 7/2018, Eesti Pank.

Rychtárik, Š., (2014), “Analytical background for the counter-cyclical capital buffer decisions in Slovakia”, Biatec, No 4/2014, Národná banka Slovenska, pp. 10-15.

Tölö, E., Laakkonen, H. and Kalatie, S. (2018), “Evaluating indicators for use in setting the countercyclical capital buffer”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 14, No 2, pp. 51-112.

See European Systemic Risk Board (2018), The ESRB Handbook on Operationalising Macro-prudential Policy in the Banking Sector, p. 26.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2010), “Guidance for national authorities operating the countercyclical capital buffer”. The European Systemic Risk Board issued Recommendation ESRB/2014/1 on guidance for setting CCyB rates in June 2014. This was followed in December 2015 by Recommendation ESRB/2015/1 on recognising and setting CCyB rates for exposures to third countries. The ESRB Handbook on Operationalising Macroprudential Policy in the Banking sector devotes a whole chapter to the CCyB.

According to the Macro-Prudential Analysis Group (MPAG): “The Basel III regulations suggest that the ratio of total credit to the non-financial private sector to GDP should be de-trended using a Hodrick-Prescott filter with a smoothing parameter of λ = 400,000 when applied to quarterly data.” See Methods for cyclical systemic risk analysis - Report of the MPAG Work Stream on Cyclical Risks Analysis.

See Lang, J.H., Izzo, C., Fahr, S. and Ruzicka, J. (2019), “Anticipating the Bust: A New Cyclical Systemic Risk Indicator to Assess the Likelihood and Severity of Financial Crises”, Occasional Paper Series, No 219, ECB.

See notifications of CCyB rates, ESRB website. Last updated 8 January 2019. Retrieved from the website on 25 January 2019. The countries in question are France, with a latest available credit-to-GDP gap of 3.3 percentage points (Q1 2018), which implied a CCyB rate of 0.5%, and Slovakia, with a gap of 3.8 percentage points, implying a CCyB of 0.5%.

See, for example, CBI (2016), Information Note: The application of the countercyclical capital buffer in Ireland.

The assessment of notifications by the ECB is required under Article 5(1) of Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 of 15 October 2013 conferring specific tasks on the European Central Bank concerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions (OJ L 287, 29.10.2013, p. 63) (the SSM Regulation).

Lang, Izzo, Fahr and Ružička (2019); Lang, J.H. and Welz, P. (2017), “Measuring credit gaps for macroprudential policy”, Financial Stability Review , ECB, May; Detken, C., Fahr, S. and Lang, J.H. (2018), “Predicting the likelihood and severity of financial crises over the medium term with a cyclical systemic risk indicator”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, May; Castro, C., Estrada, Á. and Martínez, J. (2016), “The countercyclical capital buffer in Spain: an analysis of key guiding indicators”, Working Papers, No 1601, Banco de España; Reigl, N. and Uusküla, L. (2018), “Alternative Frameworks For Measuring Credit Gaps And Setting Countercyclical Capital Buffers”, Working Paper Series, No 7/2018, Eesti Pank; O’Brien, E., O’Brien, M. and Velasco, S. (2018), “Measuring and mitigating cyclical systemic risk in Ireland: The application of the countercyclical capital buffer”, Financial Stability Notes, No 4, Central Bank of Ireland.

Babić, D. (2018), “Use of the countercyclical capital buffer – a cross-country comparative analysis”, A Review of Macroprudential Policy in the EU in 2017, ESRB, April 2018, pp. 68-82.

Lietuvos bankas (2015), “Application of the countercyclical capital buffer in Lithuania”, Teminių straipsnių serija, No 5/2015.

CBI (2018b), p. 1.

The Haut Conseil de stabilité financière (High Council for Financial Stability) is both a national macroprudential authority and a competent and designated authority for exercising CRR/CRD IV macroprudential tools in France.

HCSF (2018), Press release, Paris, 11 June 2018.

The decision by the CSSF was taken following the recommendation of the Systemic Risk Committee (Comité du Risque Systémique), the competent and designated authority for exercising CRR/CRD IV macroprudential tools in Luxembourg.

CSSF (2018), Règlement CSSF N° 18-07 sur la fixation du taux de coussin contracyclique pour le premier trimestre 2019.

This notion covers the “the approaches used by policymakers to formulate the macroprudential actions they take to achieve financial stability”. See “Comparing macro-prudential policy stances across countries”, Financial Stability Review, ECB, December 2010, pp. 133-7.

See Lo Duca, M., Pirovano, M., Rusnák, M. and Tereanu, E. (2019), “Macroprudential analysis of residential real estate markets”, Macroprudential Bulletin 7, ECB, March. See also Babić (2018); and O’Brien, E. and Ryan, E. (2017), “Motivating the Use of Different Macro-prudential Instruments: the Countercyclical Capital Buffer vs. Borrower-Based Measures”, Economic Letters, Vol. 2017, No 15, Central Bank of Ireland.

CBI (2018a), p. 2.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018a), p. 5.

See Welz and Lang (2017); and Couaillier, C. and Idier, J. (2017), “Measuring excess credit using the ‘Basel gap’: relevance for setting the countercyclical capital buffer and limitations”, Quarterly selection of articles – Bulletin de la Banque de France, No 46, Banque de France, pp. 5-18.

The underlying latest available data were from Q4 2017 and Q1 2018, respectively.

CBI (2018a), p. 2.

Babić (2018).

See NBS (2018a, 2018b, 2018c). For the composition and analytical underpinning, see Rychtárik, Š. (2014), “Analytical background for the counter-cyclical capital buffer decisions in Slovakia”, Biatec, No 4/2014, NBS, pp. 10-15.

O’Brien, O’Brien, and Velasco (2018), p. 6.

Bennani, T., Couaillier, C., Devulder, A., Gabrieli, S., Idier, J., Lopez, P., Piquard T. and Scalone, V. (2017), “An analytical framework to calibrate macroprudential policy”, Working Paper, No 648, Banque de France, October.

Lietuvos bankas (2017), p. 5.

Lietuvos bankas (2018), “Banks will have to accumulate larger additional capital buffer”, 22 June.

CBI (2018a), p. 1; Lozej and O’Brien (2018), p. 10.

Národná banka Slovenska (2018d), pp. 47-9.

Ibid., p. 50.

It could provide predictability which is key for anchoring expectations on CCyB calibrations for market participants, in order to curb excessive risk-taking by banks. “If banks adjust their expectations and thus anticipate that a buffer rate increase will be followed by further increases if excessive risk-taking continues, they may collectively reduce their risky lending.” (Babić, 2018).