- THE ECB BLOG

Inflation dynamics during a pandemic

Blog post by Philip R. Lane, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB

Frankfurt am Main, 1 April 2021

Jump to a shorter version of this blog post, which also appeared in several euro area newspapers.

In this blog post, I will provide an overview of the inflation outlook, based on the latest ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area. To set the scene, I first review the current economic situation before turning to the analysis of inflation dynamics during the pandemic.

Previewing the main messages, my assessment is that the volatility of inflation during 2020-2021 can be largely attributed to the nature of the pandemic shock: the increase in inflation during 2021 can be best interpreted as the unwinding of disinflationary forces that took hold in 2020 and does not constitute the basis for a sustained shift in inflation dynamics. The medium-term outlook for inflation remains subdued and closing the gap to our inflation aim will set the agenda for the Governing Council in the coming years.

The economic situation

The near-term economic situation continues to be dominated by high uncertainty amid the ongoing race between the roll-out of vaccination campaigns and the spread of the virus. The contraction in the fourth quarter of 2020 was milder than expected, reflecting the strong global recovery in the latter part of last year, some success in containing the pandemic and learning effects in maintaining economic activity in the presence of lockdowns. Manufacturing has held up especially well, supported by foreign demand, as indicated by the strong value of the March flash purchasing managers’ index for manufacturing. Even in the harder-hit services sector, the lockdown damage has been far less than it was during the first wave last spring.

However, the still-high level of infections, the risks posed by virus mutations and the associated prolongation of containment measures continue to weigh on euro area economic activity, especially in services, with GDP likely to have contracted again in the first quarter of this year. The further extension of lockdown measures will leave an imprint on activity in the second quarter, although the vaccination campaigns are expected to gain traction in the coming weeks.

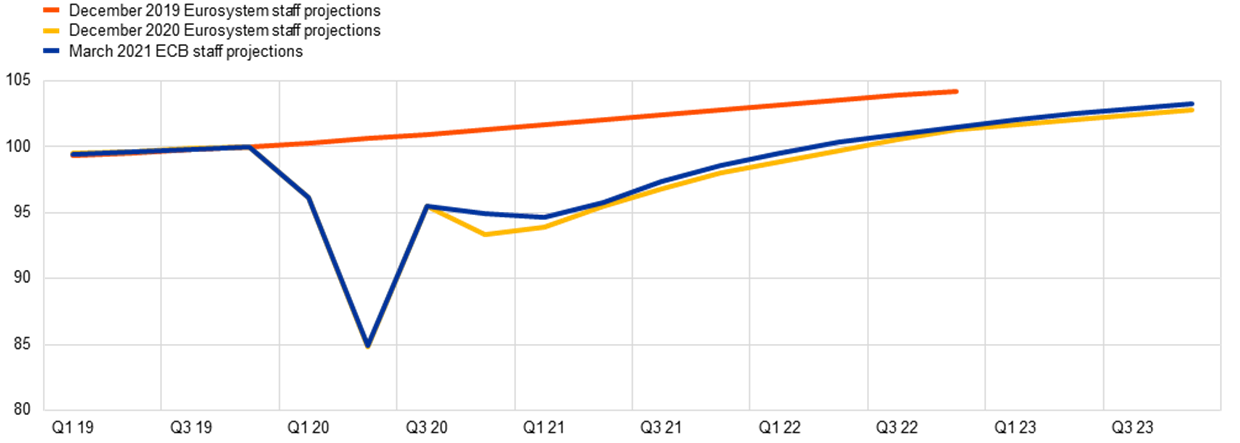

The March ECB staff projections foresee the economic recovery gaining momentum in the second half of the year as the medical situation improves and economic restrictions are eased, with output growing at a rate of 4.0 per cent in 2021, 4.1 per cent in 2022 and 2.1 per cent in 2023. Factoring in the impact of the recently adopted American Rescue Plan of the US Administration under President Joe Biden would give euro area activity a meaningful cumulative boost of 0.3 per cent of GDP over the projection horizon. However, the expectation in the baseline that GDP will reach its pre-pandemic level only in the second quarter of 2022 testifies to the vast accumulated cost of the pandemic (Chart 1).

The large uncertainty associated with the effects of the pandemic shock is captured by the mild and severe alternative scenarios developed by ECB staff. Under the mild scenario, the pre-pandemic level of activity is reached as early as the third quarter of this year; under the severe scenario, the restoration is delayed to late 2023. Of course, the 2019 output level just serves as a convenient benchmark – a full calculation of the aggregate output cost of the pandemic should take into account the pre-pandemic expected growth path over 2020-2022.

Chart 1

Selected (B)MPE projections for real GDP growth

(chain linked volumes, Q4 2019 = 100))

Sources: ECB and Eurosystem broad macroeconomic projections exercise.

Inflation dynamics

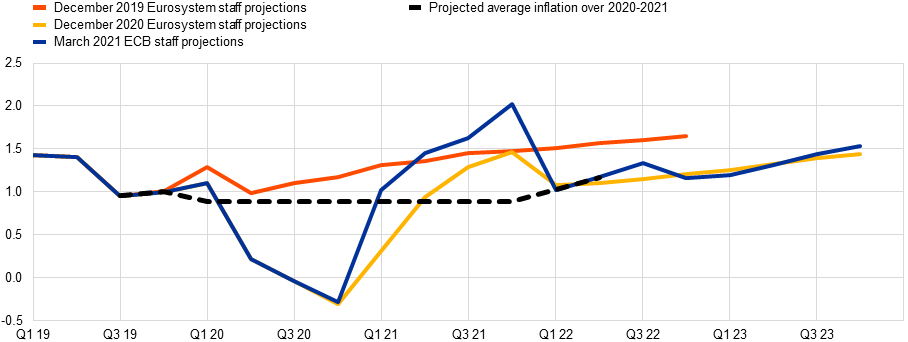

Given the sudden nature of the onset of the pandemic but its ultimately temporary nature, it should be no surprise to also see considerable volatility in inflation. As shown in Chart 2, there were substantial declines in the inflation rate over the course of 2020 (dipping into negative territory in the final months), but these are set to be largely reversed during 2021. Looking through these fluctuations, the average inflation rate over 2020 and 2021 is projected to be 0.9 per cent, which is quite close to the 2019 level.

Chart 2

Selected (B)MPE projections for inflation

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB and Eurosystem broad macroeconomic projections exercise.

Notes: The dotted line refers to the projected average of inflation during the two years 2020 and 2021.

The volatility in inflation over 2020 and 2021 can be attributed to a host of temporary factors that should not affect medium-term inflation dynamics.

First, as shown in Chart 3, the pandemic has been associated with a significant cycle in oil prices, which fell from around USD 70 at the start of 2020 to below USD 20 in late April 2020 and subsequently recovered to around the January 2020 levels; in EUR terms, the variation was slightly less pronounced due to the 6 per cent appreciation of the euro against the US dollar over this period. Under the current oil price assumptions embedded in the staff projections, this profile will generate significant base effects in energy price inflation in 2021. In addition, the introduction of a carbon surcharge on prices of liquid fuels and gas in Germany in January 2021 also contributed materially to the rebound in energy price inflation.

Chart 3

Oil price developments

(price per barrel)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The latest observation is for 26 March 2021.

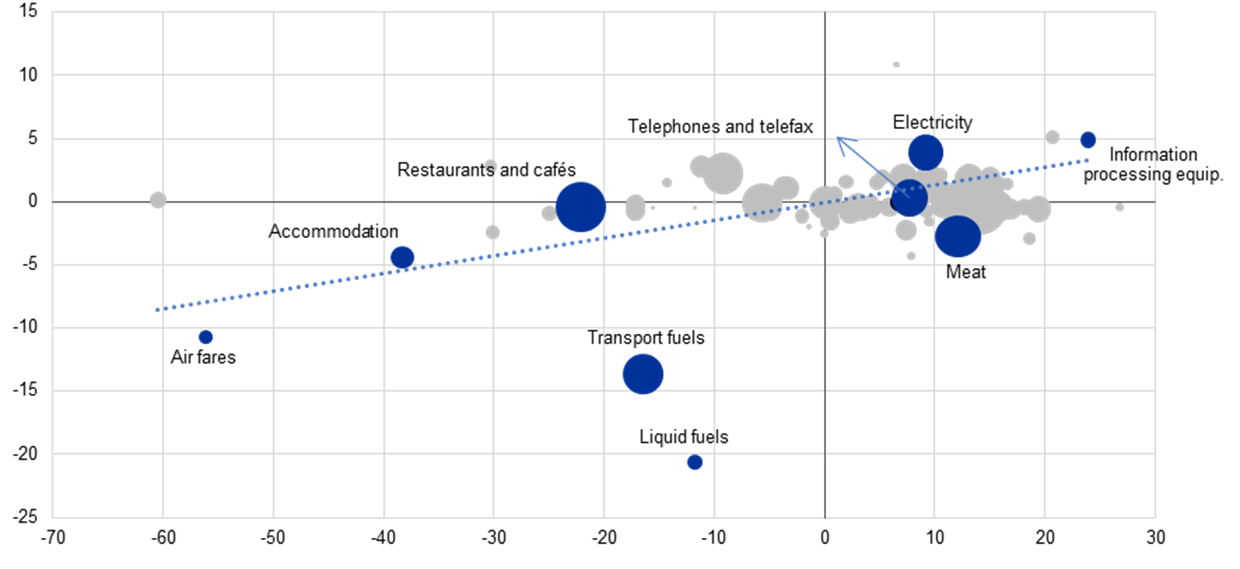

Second, the pandemic also constituted a major asymmetric shock, involving a reallocation of consumer spending across different categories, with a collapse in expenditure on tourism, travel and hospitality, in contrast with an increase in expenditure on home-related items (including groceries and equipment needed for working, learning and exercising at home). This switch in expenditure intersected with sector-specific supply restrictions to exert a significant influence on relative price dynamics. In addition, since the price index is reweighted each January to take into account the composition of expenditure in the previous year, the 2021 HICP index assigns more weight to sectors that experienced a surge in expenditure (and thereby higher pricing pressure) in 2020 compared to sectors that suffered a sharp drop in expenditure (and thereby lower pricing pressure) (Chart 4).[1] This reweighting of the price index alone accounted for 0.3 percentage points of the increase in HICP inflation in January.

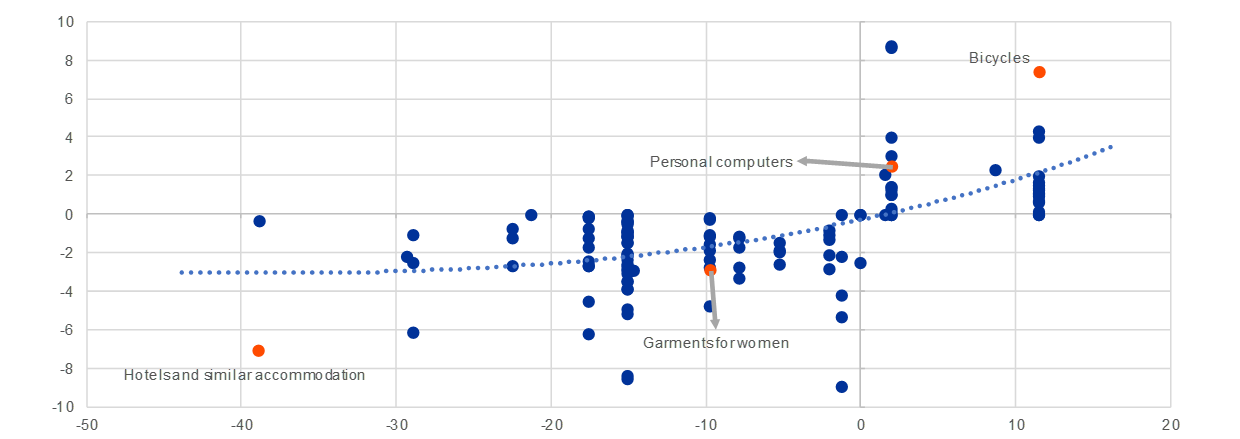

It is also plausible that the relative price movements in the pandemic had a net impact on aggregate inflation due to a convexity effect.[2] To the extent that some production inputs cannot be adjusted quickly, production functions will exhibit convex marginal costs, due to diminishing returns. In this situation, the price increases for those items experiencing a surge in demand will be larger than the price declines for those items experiencing a drop in demand: this convex pattern is evident in the cross-section of prices shown in Chart 5 and may have contributed to some “missing disinflation” during 2020, given the relatively limited decline in overall inflation compared to the drop in overall expenditure. This convexity pattern is not likely to be persistent: to the extent that the shift back to normal expenditure patterns is anticipated, demand-supply mismatches should be less severe. More generally, supply effects induced by the renewed lockdowns do not appear to be exerting upward pressure on inflation to the same extent as last spring. This is consistent with considerable adaptation and learning effects over the last year in negotiating the impact of the pandemic on production.

Chart 4

Changes in HICP inflation rates and weights

(x-axis: change between the expenditure shares used in January 2021 HICP and those used in January 2020 HICP; y-axis: scaled change in annual inflation rates between January 2021 and January 2020)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The inflation rates shown are scaled by the standard deviation of year-on-year changes in annual rates from January 2012 to December 2019. Dots that have been labelled are in dark blue. The size of the dots is scaled according to the weights used in January 2021 HICP. The latest observation is for January 2021.

Chart 5

Changes in demand and prices for goods and services

(x-axis: year-on-year change in consumption expenditure in Q3 2020; y-axis: change in inflation from January to November 2020 over standard deviation 2018-19)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Only items for which inflation and quantities move in the same direction are shown. For the methodology on the consumption expenditure series, please see ECB (2020), “Consumption patterns and inflation measurement issues during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7. Domestic flights and package holidays are excluded. The latest observations are for the third quarter of 2020 for consumption expenditure and for November 2020 for inflation.

Third, some governments (most notably Germany) implemented temporary VAT reductions that temporarily pushed down inflation in the second half of 2020 but have temporarily raised inflation in 2021 as these schemes come to an end. VAT-related base effects on HICP inflation will be particularly significant in the second half of 2021.

Fourth, inflation volatility has also been generated by the rescheduling of seasonal sales. For example, clothing and footwear sales were brought forward from January to December in Germany and postponed in Italy and France.[3] Together, such shifts imparted a large boost to the annual rate of inflation of non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) in January (to 1.5 percent from -0.5 percent), even though these have partially unwound in February with an easing back in NEIG inflation to 1.0 percent.

Finally, uncertainty surrounding the signal for price pressures is further compounded by a larger degree of price imputations, since lockdown measures interfere with the usual collection of prices for some categories.

Looking through this short-term volatility, the projected medium-term inflation rate remains subdued amid still-weak demand and substantial slack in labour and product markets: the staff projections see headline annual inflation easing back to 1.2 per cent in 2022 and only reaching 1.4 per cent in 2023. Similarly, core inflation is projected to rise only very gradually from 1.0 per cent in 2021, 1.1 per cent in 2022 and 1.3 per cent in 2023. This pickup in inflation is based on the gradual reabsorption of slack in labour and product markets, in line with the recovery in overall demand and the fading out of the adverse temporary supply effects related to the pandemic and its containment measures. In turn, the recovery in overall demand is supported by our accommodative monetary policy as well as expansionary fiscal policies at national and EU levels. In comparative terms, the projected inflation path remains well below both the pre-pandemic inflation outlook (as reflected, for example, in the December 2019 staff projections, in which inflation was projected to be 1.6% in 2022, 0.4% higher than in the March 2021 projections) and the Governing Council’s inflation aim.

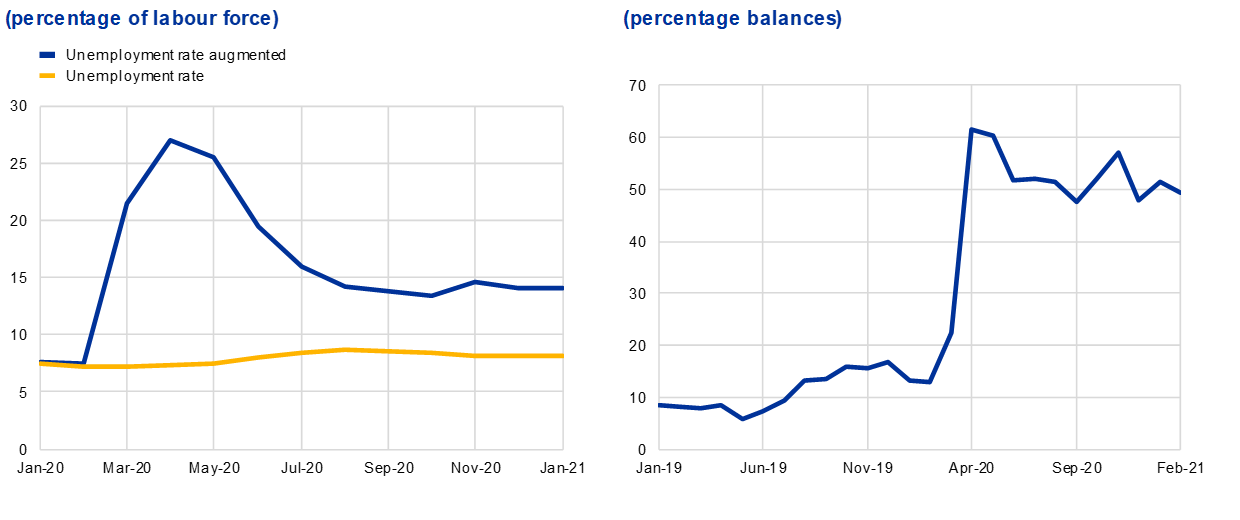

The impact of extensive slack on inflation dynamics is consistent with projected employment dynamics. The current state of the labour market is heavily shaped by the array of pandemic-related fiscal supports to firms and workers, such that the underlying prospects for employment and earnings remain highly uncertain. Although the increase in unemployment has been limited despite the vast pandemic shock, the headline unemployment figure masks considerable migration from employment straight into inactivity on the one hand and the life-support provided by the extensive job retention measures on the other (Chart 6).

The elevated uncertainty about job prospects also points to vulnerabilities ahead. Consistent with this, wages are expected to remain moderate in 2021, with wage negotiations having been widely postponed. Inactivity also damages labour productivity through the loss of current on-the-job knowledge. While the experience after the global financial crisis suggests that the wage Phillips Curve remains intact, the generation of sustained wage pressures requires a labour market that is sufficiently hot, which will require a reabsorption of a considerable amount of labour market slack.[4] Moreover, the elevated uncertainty about future employment and wage dynamics is likely to constrain consumer spending.

Chart 6

Unemployment (left panel) and unemployment expectations (right panel)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission, national sources, and ECB calculations.

The trajectory also hinges on the speed with which the spectacular rise in the savings rate during the pandemic will be normalised. While savings over the past year have partly reflected diminished consumption opportunities and partly precautionary motives, it is reasonable to expect some boost to consumption due to catch-up effects, especially in relation to activities such as restaurant meals or recreational travel. At the same time, it is plausible that households smooth out any additional consumption over time and the pandemic shock may motivate households (especially in the most-affected euro area countries) to hold some precautionary buffers. In addition, the asymmetric distribution of these savings across the population matters for the propensity to dissave after the pandemic: older and wealthier households have fared much better than younger households but the former have a lower propensity to consume (Chart 7).[5]

Chart 7

Household financial situation and savings

(change in percentage balance January 2020 – February 2021)

Sources: European Commission DG-ECFIN and ECB calculations.

Notes: The revision in household financial situation and their ability to save is proxied by the change in net balances between January 2020 and February 2021.

Turning to investment, business sentiment and expectations beyond the near term have brightened. At the same time, the sustained loss of income in the sectors most affected by social restrictions has weakened corporate balance sheets, and uncertainty about the prospects for different sectors in the economy remains pronounced. In relation to investment, firms remain likely to delay or cancel some of their capital expenditure plans against the background of heightened uncertainty about future demand for their products, spare capacity and weakened balance sheets. The significant slack in product markets may also restrain the ability of firms to raise prices, despite the desire to rebuild profit margins from their currently-compressed levels.

A high level of domestic demand (consumption, investment, government spending) is an important factor in determining overall pricing pressures, since it is plausible that the domestic inflationary pressures from these sources are stronger than from foreign demand. This is reflected in the history of euro area inflation rates, which shows a low-frequency negative correlation between the euro area trade surplus and inflation.[6]

In terms of global cost-push shocks, there are some upward pressures from higher raw material prices and bottlenecks in some sectors (including semiconductors and freight). These are expected to be temporary (reflecting mismatches between supply and demand in the initial phase of a recovery) and are also partly directly offset by the euro appreciation over the last year. More generally, the goods that are produced using such intermediate inputs do not represent a sufficiently-large proportion of the overall consumption price index for such cost push shocks to play a dominant role in determining inflation dynamics. For instance, using input-output matrices, ECB staff estimates suggest that the 38 per cent increase in global basic metal prices that occurred between June 2020 and January 2021 would only add about 1.5 per cent to economy-wide output prices: moreover, this should be interpreted as an upper bound since it neglects general equilibrium effects and assumes that the surge in prices is fully permanent. Moreover, the impact on consumer prices (compared to output prices) is likely to be rather low, since the sectors most affected have low consumption shares, except perhaps for certain electrical and transport-related consumer products. In addition, to the extent that the pass-through to output prices and consumer prices occur only gradually, the impact on the annual inflation rate in any one year will be attenuated. With the same caveats, another example is provided by the 355 per cent increase in freight costs from China to the euro area over the same period: this is simulated to generate a mechanical impact of 0.3 per cent to euro area output prices. This reflects that such a shock has a quantitatively very limited impact for most sectors, with non-negligible impacts only for some IT, textiles and transport-related products. This indicates that the likely impact in turn on consumer prices would be overall very limited.

The US Administration’s American Rescue Plan will bring positive spillovers to the euro area, even if the impact on euro area output and inflation is limited by the relatively-low trade linkages between the euro area and the United States. Holding all other factors constant, model-based simulations indicate that its peak impact via trade and financial linkages on euro area annual inflation will be about 8 basis points in 2023, although any excessive pressure on long-term nominal yields would diminish the net impact.

Longer-term inflation expectations

While the analysis so far has focused on the level of aggregate economic slack as a constraint on inflation dynamics, it is also important to recognise that inflation outcomes are also shaped by economy-wide expectations about future inflation. In particular, the subdued level of inflation in the euro area in recent years can, in part, be attributed to the weakening in expected inflation on account of the persistence of below-target inflation outcomes.

Of course, there is no single rate of expected inflation, in view of the different ways inflation beliefs are formed by households, firms and financial traders. It is also important to take into account that beliefs are formed not only about the expected inflation rate but also the distribution of future inflation rates, including the tail risks of extremely-low or extremely-high inflation rates.

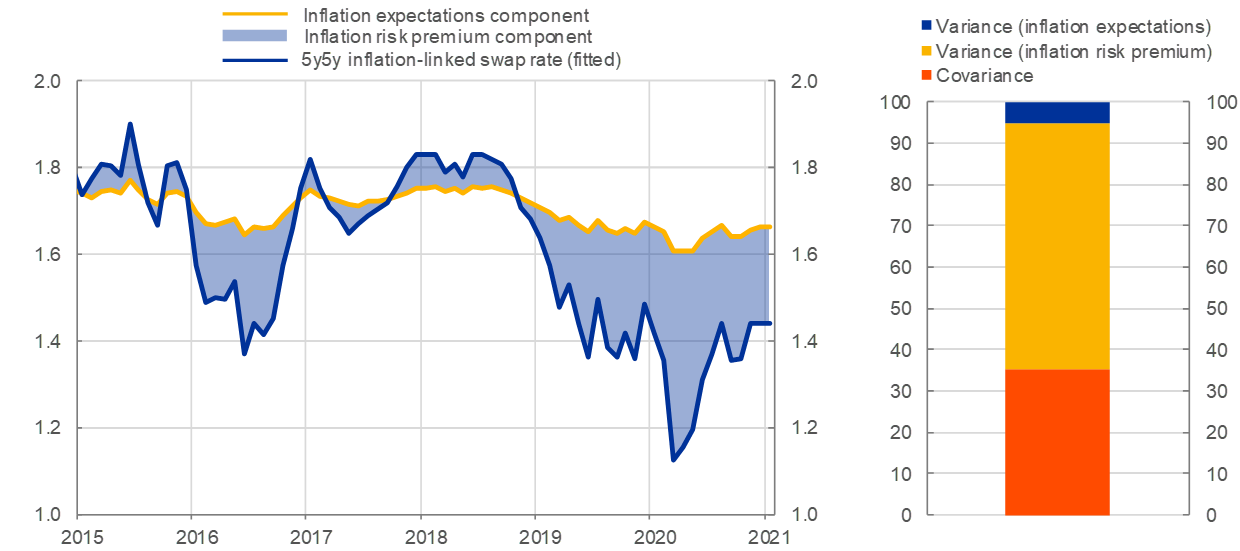

Market-based indicators of inflation compensation have increased from historic lows in recent weeks. In large part, this can be attributed to a less pessimistic global outlook, mainly related to the news about substantial US fiscal stimulus and the strong global recovery in manufacturing, trade and oil prices. In particular, the tail risk of extremely-low (or even negative) inflation outcomes has diminished, so that investors require greater compensation to hold longer-term nominal bonds, given the shift in the distribution of inflation outcomes. Of course, the recovery relative to the pandemic trough should not obscure the overall profile by which measures of inflation compensation are clearly subdued by historical standards and still at a significant distance to the ECB’s inflation aim.

Analysis of the recent evolution of some reference measures of market-based inflation compensation shows that similar but more pronounced upward moves were observed in the United States, with inflation expectations in advanced economies exhibiting a striking correlation with the price of oil. In line with this, sizeable co-movements between longer-term market-based measures of inflation compensation across jurisdictions are the norm, rather than the exception. Importantly, estimates suggest that this is not so much due to variation in the “true” inflation expectations embedded in these indicators, but primarily on account of a co-movement in risk premia (Chart 8).

Chart 8

Euro area 5y5y inflation-linked swap rate and the inflation risk premium

(percentages per annum; percentages)

Sources: Refinitiv and ECB calculations.

In relation to the inflation beliefs of financial market participants, we do not rely solely on market-based indicators but complement our assessment with lower-frequency survey-based measures, such as the quarterly ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). Survey-based measures of inflation expectations over the longer-term (for 2025) remained steady at 1.7 per cent in the ECB SPF in the first quarter of 2021.[7] It is also important to recognise the strong influence of the persistent component of inflation outcomes on beliefs about future inflation: for instance, Chart 9 shows the correlation between the average of past inflation outcomes and the evolution of long-term inflation expectations in the SPF.

Chart 9

Euro area average inflation and longer-term inflation expectations

(percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB calculations.

Analysing the full set of inflation expectations across the range of economic actors (financial market participants, firms, households) is a demanding exercise.[8] For instance, it is likely that firms and households do not revise beliefs as quickly as financial investors because of informational constraints and the logic of rational inattention on the part of many households and firms in relation to cyclical fluctuations in the macroeconomic environment.[9]

The implications of a divergence in the dynamics of inflation beliefs between financial investors and participants in the real economy (households and firms) can be illustrated with model-based simulations (Chart 10). Using the ECB-BASE model, an ECB staff analysis compares the impact on macro-financial outcomes of a generalised improvement in inflation expectations to the impact if only the beliefs of financial investors are revised.[10] In the former case, the improvement in inflation expectations has a self-fulfilling positive impact on inflation outcomes and stimulates output through the reduction in the inflation-adjusted real interest rate, despite the tightening in longer-term nominal yields stemming from an increase in term premia. In contrast, if only financial investors revise inflation beliefs, nominal yields and term premia increase but the real economy faces higher real interest rates, since the nominal tightening is not offset by an improvement in the inflation beliefs of household and firms. Under this scenario, the net impact is a contraction in output and a decline in the projected inflation path.

This analysis suggests that it is important to study carefully the evolution of inflation beliefs across all sectors of the economy. In particular, the heterogeneity across individual households and firms. suggests that significant shifts in average inflation expectations are likely to occur only gradually over time. At the ECB, the pilot Consumer Expectations Survey promises to enrich our understanding of the dynamics of inflation expectations among households across the euro area. To the extent that the inflation beliefs of financial traders are revised more quickly than the inflation beliefs of firms and households, this analysis also explains why monetary policymakers pay attention to the speed of yield curve movements, in addition to the underlying fundamentals and the interconnections between the yield curve and broader inflation developments.

Chart 10

Macro-financial implications of higher longer-term inflation expectations

Source: ECB calculations based on ECB-BASE model and the analysis by Matthieu Darracq-Paries and Srecko Zimic in ECB (2021, forthcoming) Economic Bulletin op. cit.

Notes: In all simulations we assume 0.1 increase of long-term inflation expectations. Monetary policy and the exchange rate are kept unchanged. The scenarios vary according to the perception of the shock across the various agents. In red: all agents perceive the shock (benchmark case). In yellow: all agents, except the household sector, perceive the shock. In blue: only the financial sector perceives the shock.

Conclusion

In summary, the volatility of inflation during 2020-2021 can be largely attributed to the nature of the pandemic shock: the increase in inflation during 2021 can be best interpreted as the unwinding of disinflationary forces that took hold in 2020 and does not constitute the basis for a sustained shift in inflation dynamics.

The medium-term outlook for inflation remains subdued, amid weak demand and substantial slack in labour and product markets, with the staff projections foreseeing only a very gradual increase in price pressures: inflation is projected to reach only 1.4 per cent by 2023, well below the Governing Council’s inflation aim. Accordingly, in terms of the ECB’s price stability mandate, the pandemic shock continues to pose ongoing risks to the projected path of inflation.

Against this background, ensuring favourable financing conditions is fundamental to restoring inflation momentum and guiding the formation of inflation expectations through the commitment of the central bank to counter the negative pandemic shock to the inflation path and secure convergence towards the inflation aim over the medium term. Looking ahead, it is also vitally important that fiscal support is maintained and that the euro area fiscal response to the unfolding of the pandemic and the requirements for a strong recovery is appropriately calibrated.

Offsetting the negative pandemic shock to the inflation outlook is only the first stage of the monetary policy challenge. Even after the disinflationary pressures caused by the pandemic have been sufficiently offset (with a lead role for the pandemic emergency purchase programme), we will have to ensure that the monetary policy stance delivers the timely and robust convergence to our inflation aim. Our ongoing monetary policy strategy review will provide timely input into meeting this challenge.

***

This shorter version of the blog post appeared as an opinion piece on 8 April in the following publications: L’Echo (Belgium), Politis (Cyprus), Les Echos (France), Handelsblatt (Germany), Efimerida ton Syntakton (Greece), MF (Italy), Expresso (Portugal).

The pandemic is first and foremost a human tragedy, with millions of lives lost around the world and many more suffering ill health. But it has also been a major economic shock, with fluctuations in the spread of the virus, and the social distancing measures taken to contain it, being mirrored in large swings in economic activity. For example, euro area GDP fell by 11.6 per cent in the second quarter of 2020, expanded by 12.5 per cent in the third and contracted again by 0.7 per cent in the fourth.

It should therefore be no surprise to also see considerable volatility in inflation during the pandemic period. Over the course of 2020 we saw a substantial decline in the inflation rate, which dipped into negative territory in the final months, and we are now witnessing a reversal in the first months of 2021. Looking through these short-term fluctuations, the average inflation rate over the pandemic years 2020 and 2021 is projected to be in the region of 1.0 per cent, which is quite close to the 2019 level.

The volatility in inflation over 2020 and 2021 can be attributed to a host of temporary factors that should not affect medium-term inflation dynamics. First, the pandemic has been associated with a significant cycle in oil prices, which fell from around USD 70 at the start of 2020 to below USD 20 in late April 2020 and subsequently recovered to around the January 2020 levels. The introduction of a carbon surcharge on prices of liquid fuels and gas in Germany in January 2021 also contributed materially to the rebound in energy price inflation.

Second, the pandemic also involved a reallocation of consumer spending across different categories, with a collapse in expenditure on tourism, travel and hospitality, in contrast with an increase in expenditure on home-related items, including groceries and the equipment needed for working, learning and exercising at home. Since the price index is reweighted each January to take into account the composition of expenditure in the previous year, the 2021 Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) assigns more weight to sectors that experienced a surge in expenditure (and thereby higher pricing pressure) in 2020 compared with sectors that suffered a sharp drop in expenditure (and thereby lower pricing pressure). This reweighting of the price index alone accounted for 0.3 percentage points of the increase in HICP inflation in January.

Third, some governments implemented temporary VAT reductions that temporarily pushed down inflation in 2020 but have temporarily raised inflation in 2021 as these schemes come to an end.

Fourth, inflation volatility has also been generated by the rescheduling of seasonal sales. For example, clothing and footwear sales were brought forward from January to December in Germany and postponed in Italy and France.

Looking through this short-term volatility, the projected medium-term inflation rate remains subdued amid still weak demand and substantial slack in labour and product markets: the ECB staff projections see headline annual inflation easing back to 1.2 per cent in 2022 and only reaching 1.4 per cent in 2023. This development in inflation is based on the gradual reabsorption of slack in labour and product markets, in line with the level of recovery in overall demand and the fading out of the adverse temporary supply effects related to the pandemic and its containment measures.

In our assessment the overall situation in the labour market still shows elevated uncertainty about job prospects. Although the increase in unemployment has been limited by extensive fiscal support for firms and workers, the headline unemployment figure masks considerable migration from employment straight into inactivity on the one hand and the life support provided by the extensive job retention measures on the other.

Consistent with this, wages are expected to remain moderate in 2021, with wage negotiations having been widely postponed.

In relation to overall demand pressures, it is reasonable to expect some boost to consumption due to catch-up effects, especially in relation to activities such as restaurant meals or recreational travel. At the same time, households may smooth out any additional consumption over time and the pandemic shock may motivate them to hold some precautionary buffers, especially in the euro area countries most affected. In addition, the asymmetric distribution of these savings across the population affects people’s propensity to dissave after the pandemic: older and wealthier households have fared much better than younger households but the former have a lower propensity to consume.

Turning to investment, business sentiment and expectations beyond the near term have brightened. At the same time, the sustained loss of income in the sectors most affected by social restrictions has weakened corporate balance sheets, and uncertainty about the prospects for different sectors in the economy remains pronounced. Among external factors, the American Rescue Plan of President Biden’s Administration will bring positive spillovers to the euro area, even if the impact on euro area output and inflation is limited by the relatively low trade linkages between the euro area and the United States.

Against this background, ensuring favourable financing conditions is fundamental to restoring inflation. Looking ahead, it is also vitally important that fiscal support is maintained and that the euro area fiscal response to the unfolding of the pandemic and the requirements for a strong recovery is appropriately calibrated.

Even after the disinflationary pressures caused by the pandemic have been sufficiently offset, we will have to ensure that the monetary policy stance delivers timely and robust convergence to our inflation aim. Our ongoing monetary policy strategy review will provide timely input into meeting this challenge.

- The HICP index is a Laspeyres index which weights price changes from t-1 to t by t-1 quantities. See also ECB (2021), “2021 HICP weights and their implications for the measurement of inflation”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, Box 6 and Claeys, G. and Guetta-Jeanrenaud, L. (2021), “How has COVID-19 affected inflation measurement in the euro area?”, blog post, Bruegel, 24 March.

- See also Broadbent, B. (2021), “Covid and the composition of spending,” Bank of England webinar (12 January).

- Postponements in seasonal sales also took place in Belgium, Luxembourg and Cyprus while only online sales were possible in Ireland.

- For a comprehensive review of the role of the Phillips Curve in the analysis of the economic outlook and the formulation of monetary policy at the ECB, see Eser, F., Karadi, P., Lane, P.R., Moretti, L. and Osbat, C. (2020)The Phillips Curve at the ECB, “”, Manchester School, 2020; Vol. 88, Issue S1, pp. 50–85. The authors conclude that the available evidence supports the view that the absorption of slack and a firm anchoring of inflation expectations remain central to successful inflation stabilisation. In similar vein, Bańbura, M. and Bobeica, E. (2020), “Does the Phillips Curve Help to Forecast Euro Area Inflation?”, Working Paper Series, No 2471, ECB, find that the Phillips Curve helps forecast inflation.

- Florin Bilbiie, Gauti Eggertsson and Giorgio Primiceri make the case for the United States that savings are not that excessive against the unprecedented government interventions, and are unlikely to generate a surge in demand after the pandemic – see Bilbiie, F., Eggertsson, G. and Primerci, G. (2021), “US ‘excess savings’ are not excessive”, VoxEU, 1 March.

- For a more comprehensive discussion of the role of external factors and the trade balance for inflation, see Eser, F., Karadi, P., Lane, P.R., Moretti, L. and Osbat, C. (2020)The Phillips Curve at the ECB “”, op. cit.; Galstyan, V. (2019) “Inflation and the Current Account in the Euro Area”, Economic Letters, Vol. 2019, No 4, Central Bank of Ireland; Ferrero, A. Gertler, M. and Svensson, L. (2010) “Current Account Dynamics and Monetary Policy”, in Galí, J. and Gertler, M.J. (eds.), International Dimensions of Monetary Policy, University of Chicago Press, pp. 199-244; and Corsetti, G., Dedola, L and Leduc, S. (2010) “Optimal Monetary Policy in Open Economies”, Handbook of Monetary Economics, Vol. 3, pp. 861-933, Elsevier. In principle, inflation outcomes can be insulated from this mechanism through sufficient monetary easing in response to an increase in the trade surplus. However, the correlation may be more visible in a low interest rate environment, because of the constraints on monetary policy in the neighbourhood of the effective lower bound.

- Disagreement about US and euro area inflation forecasts is discussed i.a. in the recent FRBSF Economic Letter by Glick, R. and Kouchekinia, N. (2021) “Disagreement about U.S. and Euro-Area Inflation Forecasts”.

- To this end, the index of common inflation expectations (combining 21 inflation expectation indicators) that has been developed by the Federal Reserve is a promising initiative – see Ahn, H.J. and Fulton, C. (2020), “Index of Common Inflation Expectations”, FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2 September. Recent contributions on the role of consumer inflation expectations include D’Acunto, F., Malmendier, U., Ospina, J. and Weber, M. (2021) “Exposure to Grocery Prices”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 129, No 3, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, March; Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y. and Weber, M. (2021), “How inflation expectations affect households’ spending decisions”, VoxEU, 19 March; Coibion, O., Georgarakos, D., Gorodnichenko, Y., Kenny, G. and Weber, M. (2021), “The Effect of Macroeconomic Uncertainty on Household Spending”, IZA Discussion Papers, No 14213, IZA Institute of Labor Economics; and Conrad, C., Enders, Z. and Glas, Z. (2021), “The role of information and experience for households’ inflation expectations”, Discussion Papers, No 7, Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt am Main.

- See, for example, Mankiw, G. N. and Reis, R. (2002), “Sticky Information versus Sticky Prices: A Proposal to Replace the New Keynesian Phillips Curve”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, Issue 4, pp. 1295-1328. For further discussion of households’ inflation expectations, see for example Andrade, P., Gautier, E. and Mengus, E. (2020), “What Matters in Households’ Inflation Expectations?”, Working Paper Series, No 770, Banque de France.

- For more details, see the analysis by Matthieu Darracq-Paries and Srecko Zimic in ECB (2021, forthcoming) “Macroeconomic implications of heterogenous long-term inflation expectations: illustrative simulations through the ECB-BASE”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, Box 4, ECB, Frankfurt am Main.